Church as conscience of the nation

Sometimes things come to light at the right time for a reason. Last night I found this among my archived clippings and offer it for your further meditation and knowledge.

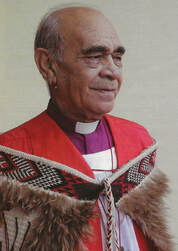

Lloyd Ashton in an eloquent profile piece on the life of Wakahuihui (to gather together) Vercoe in Mana magazine in June 2006 “The making of a radical bishop” highlighted some historical and poignant moments that are worth reflecting on in 2020.

Bishop Vercoe (Tainui, Tuhoe, Arawa, Whakatohea and Ngaitai) completed his two-year term as Archbishop of the Anglican Church in May 2006.

Yes, the bishop had his critics, he could be cranky and impatient and he said a few things that made the church and the country cringe but he stood firms on issues that are as relevant today as they were then particularly 30-years ago at the Waitangi commemorations in the Bay of Islands.

“In 1998, he was one of the leaders of the Hikoi of Hope to Parliament, to encourage a real fight on behalf of New Zealanders suffering from poverty, unemployment, bad housing, poor healthcare and schooling.

As Pihopa o Aotearoa, to help secure the 1992 constitutional reforms of the Anglican Church, whereby Pakeha Anglicans were persuaded to relax their control of the church, and to share power with their Maori and Polynesian partners.

And “his simple eloquence one summer's morning in 1990...

"One hundred and fifty years ago, a compact was signed, a covenant was made between two people... But since the signing of that treaty... our partners have marginalised us.

You have not honoured the treaty.. The language of this land is yours, the custom is yours, the media by which we tell the world who we are, are yours... What I have come here for is to renew the ties that made us a nation in 1840. I don't want to debate the treaty; I don't want to renegotiate the treaty. I want the treaty to stand firmly as the unity, the means by which we are made one nation... The treaty is what we are celebrating.

It is what we are trying to establish so that my tino rangatiratanga is the same as your tino rangatiratanga. And so I have come to Waitangi to cry for the promises that you made and for the expectations our tupuna (had) 150 years ago... And so I conclude, as I remember the songs of our land, as I remember the history of our land, I weep here on the shores of the Bay of Islands.”

[Citing New Zealand Herald, 7 February 1990.]

Ashton wrote, in his 54 years as a priest, Whakahuihui Vercoe has preached a few messages. “But chances are that none of them made people sit up and take notice the way this one did.

And it wasn't even delivered in church. On the other hand, there were a few notables in his congregation that day. The Queen, for example. Queens, in fact. Elizabeth Il, and Te Arikinui. Then there was Geoffrey Palmer, the Prime Minister of the day, and any number of politicians. Just about a who's who of heavyweights in contemporary New Zealand political life.

Queen Elizabeth was out here in 1990 for the ceremonies marking the 150th anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, and February 6 was the pivotal day of her visit. And Whakahuihui Vercoe, who was Pihopa o Aotearoa at the time, had been wheeled up by the authorities, who no doubt expected him to give a reassuring religious gloss to the proceedings. Certainly not to rock the boat. They got more than they bargained for.

When Bishop Vercoe started to speak, it was to the jeers and chants of the protestors clustered behind a police cordon. As he continued, and began to use words like marginalised', they craned forward. They fell silent.

When he'd finished, the VIPs were silent too. As in, ice-cold silent. Paul Reeves, who sat next to the Queen that day as Governor General, later reported that she'd leant over to him, to ask a question: 'Is this,’ she enquired, ‘a radical bishop?’ ‘No Ma'am,’ Sir Paul replied. ‘But he's doing pretty well.’

If Bishop Vercoe's speech hadn't been recorded by the media, there'd be no record of what he actually said. It was impromptu – in the same way, perhaps, as the messages from the Old Testament prophets were unscripted, but with plenty going on to stir them up.

‘I'd been seeing what a lot of our people in the North had to endure,’ he recalls, ‘living in derelict houses and milking sheds and so on. It was terrible. Something came upon me and I knew I had to say something.’

After that speech he got the cold shoulder from Wellington. He was never asked back to Waitangi. There were denunciations in Parliament of the troublesome bishop. And the letters to the editor tumbled in, and the talkback radio callers, predictably, spluttered with indignation. That he should be so discourteous, and behave so badly, in such distinguished company...There was support though, from some Pakeha who felt he'd hit the nail on the head.

The industrialist Hugh Fletcher, for example, sent him an encouraging note, and a gift to acknowledge the environment he'd landed in — he sent a hot water bottle. Among Maori, certainly, there was jubilation.

Bishop Vercoe hadn't been at Waitangi's Te Tii Marae the previous night.Had he been, he would have heard the late Tom Te Maro and others looking for someone who would say something to the Queen. They couldn't find anyone. ‘It wasn't till you got up,’ he later told Whakahuihui, ‘that we said: 'We didn't find him. He found us.’

And for many young Maori, there was a surge of hope. Don Tamihere, who's an Anglican vicar in Te Tai Rawhiti hui amorangi these days, was a 17-year-old in the crowd at Waitangi that day.

‘That speech,’ he recalls, ‘had a profound effect on me. It was an outstanding example of the potential of the church, of the Bishop of Aotearoa to be the voice of our people, to be the voice of God in those very serious political moments.’

In 2017 Don Tamihere was made Bishop of Tairawhiti. Today, 30-years after Bishop Vercoe's influential statement at Waitangi he is Primate or Archbishop of Te Pihopatanga o Aotearoa.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed