No solace in blood quantum

- False agenda creates division

Wrong headed thinking and deeply entrenched myths still persist in much of our outdated attitudes in Aotearoa-New Zealand as we grapple with what it is to be a bi-cultural nation that values equality and partnership.

We all bleed red but flippant and shallow judgments based on external appearance continue to create hurtful and damaging distinctions and barriers to relationships that are in desperate need of being traced, faced and replaced.

Questions such as “Are you half-caste or what percentage Maori are you?” are just plain rude. And claims there are no full blooded Maori left aren’t strictly true, I have met full blooded Maori who have strong whakapapa lines they can trace back to their waka with no tauiwi (non-Maori, foreigner) in their lineage.

Asking the percentage question suggests you might be withholding judgement until you hear an acceptable fraction. And that’s exactly what we did in Aotearoa-New Zealand until 1975 when Maori could finally choose how they voted.

The first four Maori seats were allocated in 1867 and remained unchanged until MMP was introduced in 1996. Between 1893 and 1975 if you had 50% Māori blood you had to vote for the Maori seats otherwise you were only eligible to vote for the European seats.

However, some people including the One New Zealand Foundation and its offspring Hobson’s Pledge formed in 2016, want us to return to the ‘blood quantum’ approach for determining who is Maori and therefore eligible for the so-called “special privileges and rights”.

In 2004 National Party leader Don Brash opposed Maori political seats and representation on various public boards, challenged the Treaty of Waitangi “grievance industry” and suggested there were no full-blooded Maori left.

As Pita Sharples said to the Orewa Rotary Club in September 2006, two years after Don Brash’s controversial speech, it was an unfortunate political utterance that “respect for Maori should be predicated on a level of blood quota” and that Maori were somehow a “diluted race” because of intermarriage.

He was horrified that such an argument was still being perpetuated for political gain, stating “identity cannot be measured in parts”.

As recently as 2013 One New Zealand Foundation, in a submission to the Ministry of Justice said it would be fairer to all New Zealanders if the definition of Maori in any future Constitution stated, “Maori must prove they have 50% or more of tangata maori ancestry/blood quantum” to be legally considered Maori.

Researcher Ross Baker asked people raise the ‘blood quantum issue’ in their own submissions to the ministry. “Why should a New Zealand Citizen with less than 50% of ‘tangata maori’ ancestry have privilege, advantage or extra rights over any other New Zealander?”

These ideas continue to be propagated by Hobson’s Pledge which actively campaigns against Maori rerpresentation on councils and its idea of ‘Maori privilege’ despite the clear need to continue addressing the many issues of inequality evident in our society that can be traced back to broken Treaty promises.

Not so black and white

I’ve even begun to wonder if trying to squeeze Maori into a blood quantum framework on top of the land confiscations, other treaty breaches and attempted assimilation by church and state to “become like us”; the “we are all one” rhetoric, hasn’t actually been a kind of identity theft.

So where did this idea of black and white representing superior and inferior come from; was it a tactical tool for colonisation and is it something we need to personally and nationally ‘repent’ from?

Going way back to biblical times it was hardly a factor; if there was an issue of division it was more about religious, cultural or territorial issues. The Hebrew or Jewish people were connected by their genealogical ties back to the original 12 tribes, regardless of skin colour

Simon of Cyrene who was forced to carry the cross for Christ was from modern day Libya and most likely an African man. Paul regularly hung out with Barnabus a native of Cyprus (often depicted as dark skinned) and Simeon (also known as Niger meaning of dark complexion) were close partners in sharing the Gospel.

The Ethiopian Eunuch was an influential person who spread the Gospel to his own people after an encounter with Phillip (Acts 8:26-40). And of course it mustn’t be forgotten that Jesus (Yeshuah) himself was not some blue-eye blond, he was an indigenous Middle Eastern most likely of a swarthy brown complexion.

Skin pigmentation went from simply being a fact of life based on location and genetics into a cultural and class determination in 1600s America largely because of the slave trade.

Britain had colonised American and was in need of labour to create its new reflections of empire building infrastructure and working the land taken from native Indian tribes or working in plantations.

Initially white Irish were imported to do the work, as they were apparently not considered fully human under British law. They worked sugar cane plantations in the Caribbean but more labour was needed so the Atlantic slave trade with Africa was born, often through seducing people on board ships or because chiefs or tribal elders sold off their own people for profit.

Bonded blackmail

Bonded labourers were often set free after paying back the amount they were allegedly in debt for, and intermarriage often created a peasant class who were increasingly used as labourers

Whiteness, and blackness as a language for race was born in the mind of America in Virginia around the 1680s, and seems to first appear in Virginia law in 1691. Whites were given certain rights, while existing rights were taken from blacks (negroes, mulatos or Native Indians).

Black and white slave owners and land owners both had the vote until early 18th century but when the law shifted so whites could no longer be permanently enslaved, black slaves lost the ability to work their way to freedom.

Whites, even poor ones were now considered to be above blacks accelerating the race distinction or racism that was affirmed by Darwin’s survival of the fittest theories from the 1850s, creating a blueprint for further advancing colonisation across the globe.

Blood quantum, the determination of someones make-up by the percentage of racial parentage, is still used to some degree in the United States.

It originated with The Indian Removal Act (1830) and the resulting Trail of Tears or forced relocations of approximately 60,000 Native Americans, and efforts to create a head count.

Many forcibly driven from their ancestral homelands were well aware they were being “subjected to genocide” and understandably mistrusted the government of the time and tried to flee.

If they weren’t already in “prison camps” warrants were issued for their arrest and they were forcibly rounded up and documented against their will...this enrollment was not optional.

From 1834 the Indian Reorganization Act required persons to have a certain blood quantum to be recognized as Native American and be eligible for financial and other benefits under treaties or sales of land.

Someone with an Indian grandparent and three non-Indian grandparents was determined to be one-quarter Indian blood. Tribes that use this method require at least one-half to one-sixteenth tribal blood with proof required through documents approved by a government or tribal official.

Some tribes require as much as 25% ‘blood quantum but most still allow one sixteenth or one great grandparent. This is specifically prescribed under the US Federal Acknowledgment Act, 1978.

A Certificate of Indian Blood (CIB) can be obtained from the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) a regional or agency office that covers a tribal area closest to where ancestors lived or the tribe is located.

These Indian blood laws in the US and the 13 colonies that define Native American identity were enacted by the US Government, although some tribes no longer have this as part of their criteria.

Half blood to vote

In New Zealand the definition of Maori for electoral roll and other purposes, up until the late 1970s at least, was an expectation of 50% or greater Maori lineage.

Richard Mulgan in his book Maori, Pakeha and Democracy puts it simply. “Until 1981 the census defined a Maori as someone with a half or more Maori ancestry. The electoral law was similar. Before the Maori option for voter registration was introduced in 1975, voters were Maori or European electoral roles according to the fractions of their descent, with half castes being allowed a choice of either role.”

He says such definitions in terms of the degree of descent entirely ignored the cultural element in ethnic identity. “On present day views of ethnicity it is the cultural aspect which is now paramount. The key issue for someone of mixed ancestry is which ethnic group he or she is identified with.”

The 1986 census instead of requiring a precise fraction of descent, simply asked people for their ethnic origins with the Maori option for parliamentary elections allowing anyone with at least one Maori ancestor the option of enrolling on either the Maori or the General roll.

New Zealand’s Ministry of Social Development (MSD) is clearly still wrestling with the issue in its paper, The problem of defining an ethnic group for public policy and why does it matter? It reviews multiple attempts to measure Maori identity through biology, socio-cultural or ethnic group attachment.

It cites Ritchie’s “degree of Māoriness” scale (1963) and Metge’s schema of “Māoritanga” (1964) and more recent researchers from Massey University who proposed a single measure of Maori cultural identity after a study of Maori households.

The measure is a weighted aggregate of an individual’s scores on seven cultural indicators (Cunningham et al. 2002, Stevenson 2004). Māori language has the highest weighting, followed by involvement with the extended family, knowledge of ancestry, and self-identification, based on a subjective assessment of the contribution of each to a “unique Māori identity”.

The paper presupposes that there is something culturally unique about Māori, and “that this can be prioritised, quantified and aggregated”. Elsewhere, researchers have used language use, religious affiliation and/or network ties as measures of ethnic attachment (Reitz and Sklar 1997).

Their problems with definition seem to be highlighted because of the diffulty in distinguishing between single-ethnic and multi-ethnic peoples and inter-marriage which “dilutes ethnic identity, which in turn weakens group solidarity and concomitant claims based on cultural uniqueness (Birrell 2000)”.

From a policy perspective, MSD says the distinction between single- and multi-ethnic persons is “easier to operationalise than either cultural indicators or biological proofs” making it more likely. to be accepted by policy makers as a way of dealing with those “deserving of closer attention”.

MSD certainly makes every effort to sound like its done its homework in order to background the reasons it believes what it does, in order to meet Maori needs.

Recipe for division

But these are deep identity issues that need careful handling as Maori move into the new way of asserting an identity that has been undermined and classified and reframed often in demeaning ways for far too long.

Donna Matahaere-Atariki, who received the NZ order of Merit in 2018 for over 20-years service in Maori health and education, recalls, in her Cultural Revitalisation thesis (2016), says the 1950s for example was a tense time for mixed marriages with resistance from both Pakeha and Maori to such unions.

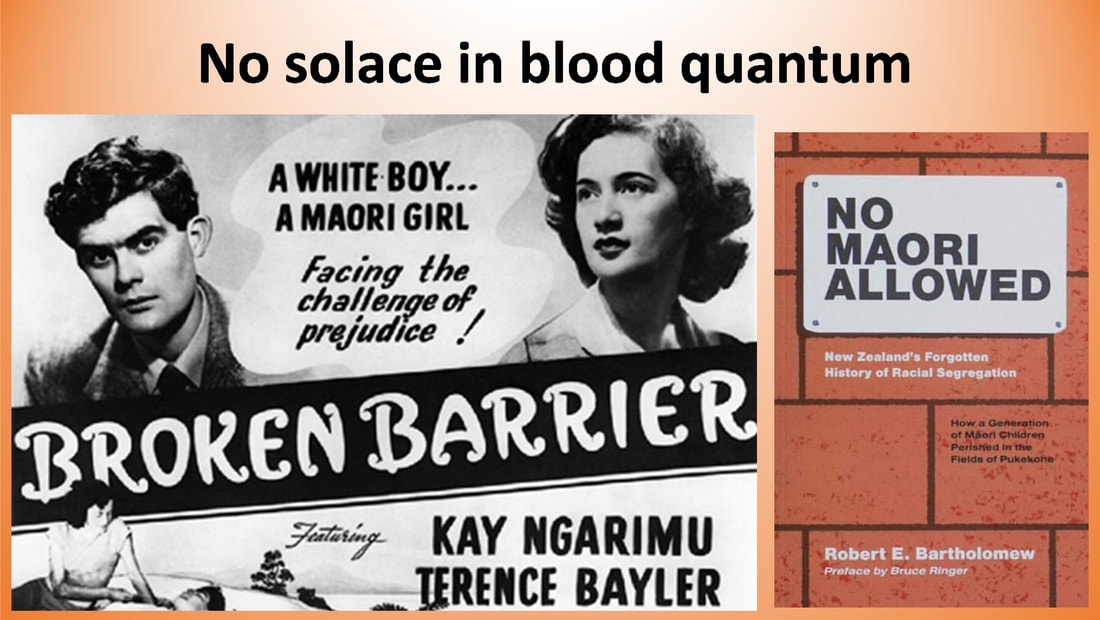

She says the 1950s movie Broken Barrier which dealt with the issues of intermarriage helped promote New Zealand on the international stage as an exemplar for racial tolerance which clearly was far from the truth.

“As a child of mixed marriage I was often reminded of the term half-caste, a term that was intended to be inferior. I recall being in High School during the 1970s and the teacher asking all children of any Māori descent to stand so that we could be counted. I was unaware at that time that this instruction coincided with government policy that changed the caste system from a belief in blood quantum to one of descent. An older birth certificate notes that I am ‘3/4 caste’.”

Matahaere-Atariki says degrees of descent remain problematic because this normalises the tendency for identity to be confused with biological features. “Even today, the notion of blood quantum can be used as a self-identifier of an individual’s ‘degree of Māori-ness’ which is disconcerting.”

She quotes Angela Wanhalla discussing the difficulty of tracing mixed marriages, specifically for Māori women citing multiple research projects which stated very few full blood Māori exist, thereby “legitimating both a turn to racial traits and a refusal to recognise the rights of a fully endowed indigenous population”.

Matahaere-Atariki says, “If we do not exist ‘in all our purity’, then it is assumed that we have no rights. The concern that mixed marriages weakened group identity based on ideas of cultural uniqueness is both unhelpful and scientifically indefensible. Politically it represents the exposure of racial ideology promulgated in order to conjure up a platform for the disenchanted.”

She says the term “cultural revitalisation” is an incomplete term “for the right to continually remake our culture and identities in ways that we may yet, not even imagine. We carry our fears in a way that our mokopuna do not. They will have opportunities, yet to be discovered, and it is the role of all of us, including government to ensure that policy is broad and deep enough to support their right to express their culture with the technologies at their disposal.”

Culture, she says, should be an ordinary part of what defines Maori and not a burden to be recovered.

Race is arbitrary

New Zealand-born mission leader, author and communicator John Dawson says biologically there are no races and so-called racial characteristics vary so much from individual to individual that all attempts at establishing distinct biological units that deserve classification are arbitrary.

“Each person has tens of thousands of different genes. At the genetic level, human beings are incredibly diverse in a way that transcends geographical dispersion. Therefore, what we call a race is a classification of culture, having more to do with tribal membership or national citizenship than any real genetic distinction.”

For some reason, says Dawson in his book Healing Americas Wounds, skin colour has been the defining characteristic in cross-cultural relationships. “No personal physical feature, except gender, has made such an impact on the fates of individuals and people groups, yet pigmentation is a relatively superficial thing.”

Pakeha can be cruel when we speak in racist clichés like ‘bloody Maori’, fail to engage meaningfully, use ‘get over it’ terminology in relation to unresolved Treaty issues or suggest Maori shouldn’t be privileged over any other race.

Just read the comments column in the newspapers around Treaty settlement articles or for that matter social media. If you hadn’t noticed racism has become a major issue in recent years then you have grown an extra thick skin, regardless of its colour.

The book No Maori Allowed by Robert E. Bartholomew (Feb 2020) which exposed deeply entrenched racism in Pukekohe and other locations in South Auckland in the 1950s-1960s was an eye-opener for many.

That skin colour was used to prevent Maori sitting in the same theatre rows as their Pakeha friends, getting their hair cut at the same barber shop or being served at the same pub was one of those shameful things few spoke about other than in hushed tones in selective company.

It was heartening to learn that the segregation in the local theatre came to an end when Pakeha friends of Maori who were being discriminated against took a stand and confronted the owner. It would be interesting to know whether Maori felt welcome in local churches and whether those churches stood with them?

Restoring our story

Similarly the overt racism of publishers, politicians and property peddlers in Taranaki and Whanganui in the 1860s – 1880s; misinterpreting the works of Darwin to place Maori lower down the evolutionary scale than them, was too often casually dismissed.

The use of race and colour was used alongside greed without conscience as a further impetus to usurp Maori land, rights and mana.

The attitude in Pukekohe and neigbouring townships in the 1960s is in living memory and is far too close for comfort for those who still see colour as a barrier as were the attitudes of white superiority among far too many of us outed into the mainstream following the Christchurch mosque massacres.

History needs to be revealed warts and all if we are to progress as a nation. Our attitudes and loose lips are rightly under scrutiny as are those of many of our major organisations being exposed as institutionally racist.

If we are all created in the image of God (Latin: Imago Dei; Gen 1:27) then technically we’re divinely related and need to aspire to a higher calling that affords dignity to the diversity of our nation’s composite make-up.

There’s no question the multi-cultural blend will continue to shift and change through immigration and mixed marriage but at a foundational level we are a nation founded on a treaty between two peoples.

If those two Treaty partners can’t get it together and figure out how to walk in greater synchrony then in a rapidly evolving world where social, political and technological parameters are rapidly shifting we should expect major disruption and instability ahead.

Looking back historically can be helpful and informative but there’s a need to lift the carpet, look closely at what we’ve swept under there, and get to work at cleaning our respective houses so the next generation isn’t left with our mess.

Myself and others have been musing lately on the word ‘repentance’, as a pre-requisite for a changed life. It’s much more than asking ‘forgiveness for sins’ which in itself sounds like the start of one of those fire and brimstone messages that turned so many off investigating the Christ-based life.

The word first came alive when I read a secular book in the early 1980s that translated it as “having a fundamental, childlike transformation of mind”. That resonated. In a recent study on the Bible & Treaty site by the studious James Hay, he saw an immediate application for justice and reconciliation in terms of the Treaty of Waitangi.

In the New Testament repentance is a major theme; its used 64 times ( Gr: meta = after; noeo = to perceive; nous = the mind), and unpacks as to perceive afterward, to look back and regret or be moved when you see the consequences of your actions and change or amend your way of thinking and acting.

Rather than a guilt inducing religious term it actually asks us to look at how we think and whether this is appropriate going forward. James applied the term to being honourable and truthful, acting righteously and on becoming aware of the error of your ways, like Zacchaeus, working generously to restore what has been wrongfully taken.

Yes indeed, we need to get over our racist selves and show some long overdue respect and indeed generosity. Trying to re-classify anyone according to their blood quantum will offer no solace or solution to any social problem because who we are and who we are becoming defies such definitions.

It doesn’t require everyone to agree on how to approach kotahitanga (unity), just a groundswell of visionaries and leaders, including those in the church, who believe we can do things better, and are prepared to actively and intentionally listen and become part of the shift into a more positive and co-operative space.

If more of us saw Maori and Pakeha as equal partners, changed our way of thinking about race and colour, and stepped up to the higher calling as spiritual beings embracing the kind of love that transcends such pettiness we might even change the course of the nation.

Sources and resources

Ross Baker, Researcher, One New Zealand Foundation Inc, submissions to Ministry of Justice. April 2013.

Richard Mulgan, Maori Pakeha and Democracy, Oxford University Press, 1989, p.14

Donna Matahaere-Atariki, Cultural Revitalisaiton and the Making of Identity within Aotearoa New Zealand, , thesis, 2016

John Dawson, Healing Americas Wounds, Regal Books, California, US, 1994, p.205

RSS Feed

RSS Feed