Origins of the Treaty of Waitangi

While the British, had showed little respect for the peoples they would subjugate and often turn into slaves, a new conscience had entered public thinking ahead of any colonial plans for New Zealand.

If colonised at all, this was to be done differently, in partnership with the indigenous people.

Both the historic agreement that bought together the United Confederation of Tribes to declare independence and select a flag, under which New Zealand built trading ships could legally operate on the high seas, and the subsequent Treaty of Waitangi, would not have been possible without the influence of the missionaries.

Wilberforce influence

Several decades before the Treaty was signed both slavery abolitionist William Wilberforce and others who were part of the humanitarian Clapham Sect backed the Church Missionary Society (CMS) and a missionary move into New Zealand.

Wilberforce himself was an active patron to Samuel Marsden who would eventually preach the first Christian sermon on New Zealand shores in 1814 at the invitation of Maori chief Ruatara.

The more humanitarian attitude championed in part by Wilberforce and his legal counsel, friend and later brother-in-law James Stephen, who together bought an end to the slave trade, extended to the new generation of influential humanitarian Christians.

It was James Stephen’s son, who as British Colonial Secretary, gave the instructions to Lord Normanby ensure Hobson set out the mutually beneficial principals of agreements that became known as the Treaty of Waitangi.

Stephen was well aware of the atrocities that had been perpetuated on the indigenous people of other nations by the process of British colonisation and was determined that this was never to happen in New Zealand.

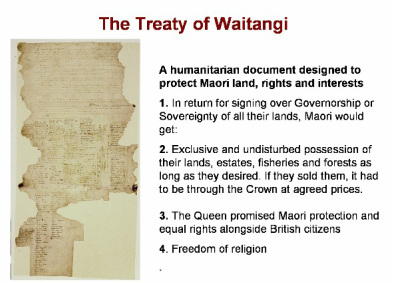

Maori land and resources were to be protected by law and they were to be treated as equal rights citizens with the British.

Faithful translation

Hobson then asked Henry Williams and his son Edward to translate a document he’d been working on to best represent the intentions of the Colonial Office.

Williams and son, who were both fluent in the Maori language, knew the words that would convey the intent of this covenant, which they hoped would not only bring British law to govern the unruly activities of British citizens but protect Maori from ruthless landgrabbers and give them a say in what happened in their own land.

The missionaries were tasked with ensuring Maori knew the meaning of the treaty and of going about the country helping the Crown representatives gain signatures on this historic document.

Sadly within three years of the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, when the humanitarian Christians had gone from the Colonial Office, both missionaries and Maori were faced with clear evidence that they’d both been betrayed.

While much has been done in the past 40-years to put right those injustices, that lingering sense of pain and betrayal is still being worked through as New Zealand continues to face up to the dark years and find ways to fulfil the Treaty promises of he iwi tahi tatau or two peoples together as one nation.

If colonised at all, this was to be done differently, in partnership with the indigenous people.

Both the historic agreement that bought together the United Confederation of Tribes to declare independence and select a flag, under which New Zealand built trading ships could legally operate on the high seas, and the subsequent Treaty of Waitangi, would not have been possible without the influence of the missionaries.

Wilberforce influence

Several decades before the Treaty was signed both slavery abolitionist William Wilberforce and others who were part of the humanitarian Clapham Sect backed the Church Missionary Society (CMS) and a missionary move into New Zealand.

Wilberforce himself was an active patron to Samuel Marsden who would eventually preach the first Christian sermon on New Zealand shores in 1814 at the invitation of Maori chief Ruatara.

The more humanitarian attitude championed in part by Wilberforce and his legal counsel, friend and later brother-in-law James Stephen, who together bought an end to the slave trade, extended to the new generation of influential humanitarian Christians.

It was James Stephen’s son, who as British Colonial Secretary, gave the instructions to Lord Normanby ensure Hobson set out the mutually beneficial principals of agreements that became known as the Treaty of Waitangi.

Stephen was well aware of the atrocities that had been perpetuated on the indigenous people of other nations by the process of British colonisation and was determined that this was never to happen in New Zealand.

Maori land and resources were to be protected by law and they were to be treated as equal rights citizens with the British.

Faithful translation

Hobson then asked Henry Williams and his son Edward to translate a document he’d been working on to best represent the intentions of the Colonial Office.

Williams and son, who were both fluent in the Maori language, knew the words that would convey the intent of this covenant, which they hoped would not only bring British law to govern the unruly activities of British citizens but protect Maori from ruthless landgrabbers and give them a say in what happened in their own land.

The missionaries were tasked with ensuring Maori knew the meaning of the treaty and of going about the country helping the Crown representatives gain signatures on this historic document.

Sadly within three years of the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, when the humanitarian Christians had gone from the Colonial Office, both missionaries and Maori were faced with clear evidence that they’d both been betrayed.

While much has been done in the past 40-years to put right those injustices, that lingering sense of pain and betrayal is still being worked through as New Zealand continues to face up to the dark years and find ways to fulfil the Treaty promises of he iwi tahi tatau or two peoples together as one nation.