Refocusing for the future

By Keith Newman (02-02-22)

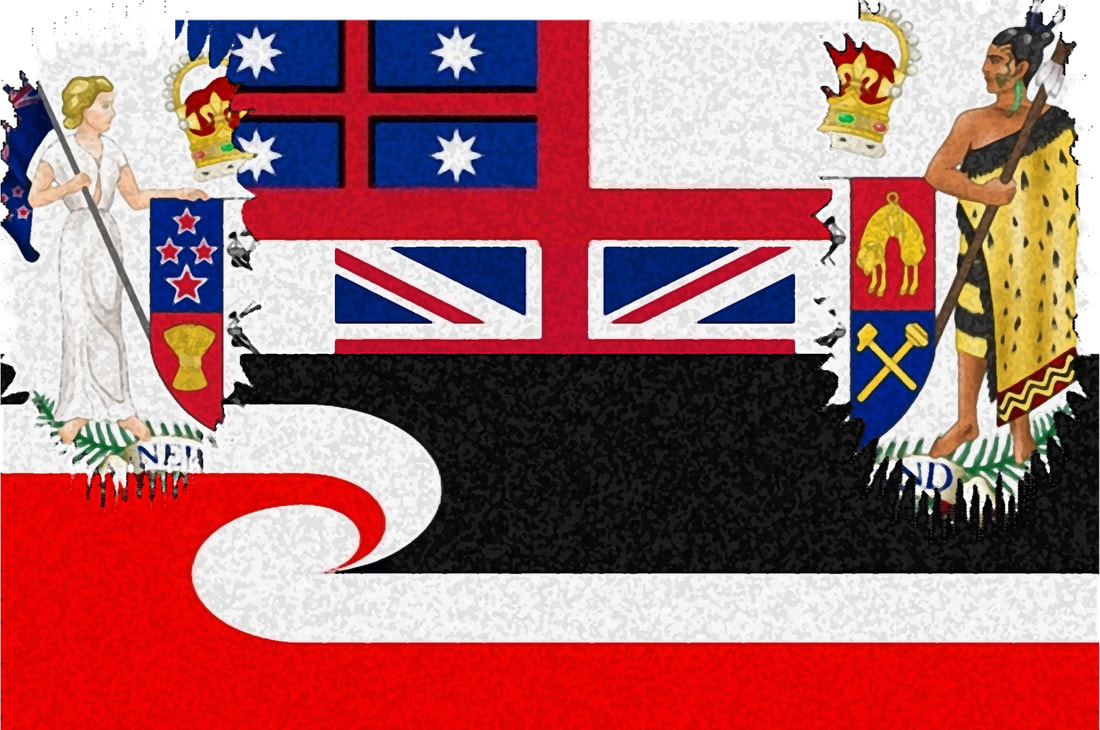

Aotearoa-New Zealand might not have a cohesive constitution or a clear mission statement but we do have three hurriedly translated, often misinterpreted paragraphs, that provide the foundation promises for forging a formidable future together.

Alongside that founding document there’s an equally misunderstood statement, sealed with a hongi and a handshake, that urges Maori and Pakeha to look past the barriers of difference and work together for the common good.

On 6 February 1840, British officials and church leaders including Church Missionary Society head Henry Williams and Catholic Bishop Pompallier were at Waitangi in the Bay of Islands to witness the Treaty of Waitangi being signed by Maori chiefs and the Crown.

Maori wanted protection from the lawlessness of whalers, sealers and traders and were concerned that private investors were claiming enormous quantities of land for blankets and buttons, pots and pans, tobacco, gunpowder, tools and small amounts of cash. There was also the very real possibility of the French making a claim to the country.

The treaty promised Maori exclusive and undisturbed possession of their lands, estates, fisheries and forests as long as they desired (tino rangatiratanga/ chieftainship). Their land could only be sold at agreed prices through the Crown (pre-emption). In exchange Maori would concede elements of governership (kawenatanga) or sovereignty, terminology that is still the subject of heated debate.

Queen Victoria, representing the Church of England, promised Maori protection and equal rights and privileges alongside British citizens. Maori looked forward to more lucrative trading opportunities, confident their lands would be protected unless they wanted to sell and saw this new relationship with the Queen as affirming the biblically-based principals behind 30-years of missionary teaching.

This was not an invasion or colonising in the sense of how Britain had dealt with countless nations previously. This was a deal with a very intentional Christian undercurrent to ensure such colonizing atrocities on indigenous people, never happened again.

Maori, based on the He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tireni (Declaration of Independence of the United Tribes of New Zealand) signed with Britain five years earlier were an independent people with their own form of agriculture and tribal governance.

Ultimately 540 Māori chiefs signed nine copies of the Treaty of Waitangi, including 13 women; all but 39 signed the Maori version.

While the Treaty assured equality with British citizens, French Bishop Pompallier wasn’t entirely happy with the thought that the recently arrived Catholics might be sidelined so he insisted on a fourth clause covering freedom of religion.

This often ignored ‘phantom clause’, written down on the day and recorded by William Colenso in his report but not signed as part of the Treaty, may yet prove as invaluable as other oral history.

Peaceful alliance

A treaty is often viewed as a peace alliance and this one was a peaceful bilateral agreement. It was certainly not the signing over of everything one party had to the other.

Once Maori signatures or tohu (symbols) were placed on the treaty document that first Waitangi Day, Governor William Hobson greeted each chief with a sincere He iwi tahi tatou. That’s had various interpretations imposed including ‘Now we are one people’. In recent years it has often been written as He iwi kotahi tatou which affirms that interpretation but has added to the confusion.

Some writers, including Danny Keenan go so far as to suggest Hobson never made that statement and it was added later by eye-witness to the events, missionary printer William Colenso. And of course the term has come into disrepute because of its use by the ‘Kiwi not Iwi...one New Zealand’ advocacy group Hobson’s Pledge which holds to a literal interpretation opposing any hint of ‘Maori privilege’ including separate political representation.

Social anthropologist and writer Dame Joan Metge doesn’t seem to have a problem accepting what Hobson said but suggests it might be better understood to mean “We two (many) peoples together make a nation”. Another scholarly Dame, researcher and writer Ann Salmond views the treaty as “...a chiefly gift of exchange” involving shared humanity, reciprocity and respect.

Ngāpuhi elder Waihoroi Shortland stepped into the debate at the Waitangi Day commemoration in 2020 when he challenged Governor-General Dame Patsy Reddy insisting it was time to address the modern misuse of Hobson’s words. The words Hobson was “encouraged to say” were, ‘he iwi tahi tātou’. “He did not say, ‘he iwi kōtahi tātou’.”

It was an unresolved issue that needed to be corrected. Shortland said the northern tribes understood the difference, and it related to the uniting of Maori and Pakeha. He translated them for the Governor-General as, ‘Together we are one nation’.

Who influenced Hobson?

Stepping back in time we might ask where the phrase He iwi tahi tatou came from? Was Captain Hobson simply ad-libbing or ‘encouraged’ to say those words as Shortland suggests.

There’s every indication the source of that encouragement was Henry Williams, who with his son Edward translated the Treaty of Waitangi virtually overnight, having just arrived back in the Bay of Islands after travelling overland from the Kapiti Coast.

The original treaty instructions to be interpreted in te reo Maori had come from the James Stephen Jnr, permanent under-secretary of the Colonial Office, a committed Christian and the nephew of William Wilberforce, British Parliamentarian, slavery reformer and mentor to Samuel Marsden.

Williams drew on biblical concepts and his previous effort in translating He Whakaputanga for the treaty clauses and the suggested Maori words for Hobson to affirm the signing would not have been chosen lightly.

Hobson’s so-called pledge had him quoting from Galatians 3:26-29 where the Apostle Paul says “for you are all one”. The context makes it plain that this is about becoming sons and daughters of God through faith in Christ, and that the unity being spoken of is a spiritual connection that does not favour one people group over another.

Taking the phrase literally creates immense difficulty and confusion if we read the rest of the verse, which states that those who embrace this challenge are now “neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female”.

Maori, who had sat under the missionary teaching for over 26-years, would have known that this treaty was about becoming part of something new that was not based on old tribal divisions.

The treaty wasn’t simply signatures on a piece of paper, it was a spiritual and political covenant, a marrying of two peoples, with an expectation that both would benefit and do amazing things together with their shared energy and resources.

Maori voice silenced

All good covenants and treaties, and indeed marriages, require ongoing conversations to check on progress, to determine if the conditions are being fulfilled and concerns addressed. For Maori that failed to happen.

Despite the best intentions of those wrote, promoted and signed the treaty it’s basic promises and the affirmation of unity were soon betrayed. New Zealand was essentially being run from New South Wales and Hobson and his band of officials had little funding or support to run this new outpost of empire.

From about 1843 onward the treaty seemed of little importance and people like Henry Williams who helped transcribe it were dismayed at the failure of the Crown and its representative to honour it as clear breaches were ignored and armed confrontations escalated.

Massive land sales were being transacted and often the promise of adequate reserves and hospitals and schools disappeared as quickly as the surveyors arrived. The pressure remained to acquire tribal land, break customary ownership and force individualisation of Maori title to meet the demands of settlers.

The initial problem was created by the New Zealand Company which had sold what they hadn’t yet properly purchased before Crown land purchasing officers began engaging in similar underhand tactics.

The Treaty of Waitangi was an obstacle to greedy politicians, lawyers and land agents acquiring lands as cheaply as possible and then on-selling it for profit to top up government, individual and investor coffers.

The Maori voice was effectively silenced. Even a long line of advocates including the Williams brothers, Colenso, Octavius Hadfield and later Maori prophets and kings achieved only a token hearing when they raised concerns about the obvious betrayals and injustices.

When Maori began to resist, organize, question, challenge and pull out surveyor’s pegs, military campaigns were mounted by successive governors with tactical laws passed that supported dispossession, including confiscating ‘rebel’ land in the richest parts of the country.

Retrieved from the rats

There was little conversation about the Treaty of Waitangi in the years after it was signed. Promises of gatherings to discuss next steps never happened.

There was no hint in the four original treaty clauses or the four words that sealed that deal with a handshake and a hongi of assimilating Maori into a colonial melting pot, as some future administrators imagined when they essentially excluded Maori from the 1852 Constitution Act and spoke of “fluffing up the pillow of a dying race”.

The treaty was soon forgotten, lost, nibbled at by rats and saved from a fire. In 1877 it was undermined in the courts when on high court judge declared it “a simple nullity” because ‘the savages’ who signed it could never have understood what they were doing.

But Maori were resilient and determined to ignore the false prophecies and despite being worn down by war and deception new visionary leadership set them on a road to restore their rightful place in the land they one called their own.

Maori prophet Tahupotiki Wiremu Ratana and Kingitanga leader Tupu Te Waharoa raised a petition with full evidence of treaty breaches, signed by two thirds of all Maori (40,000). Despite efforts to undermine it in England and in New Zealand, it was eventually tabled in Parliament in 1932 with the proposition that it be ratified and included in the laws of the nation. Still, it languished.

Then the Treaty of Waitangi became the heart of the Maori renaissance of the 1970s when a new generation of activists could no longer tolerate the duplicity. The Waitangi Tribunal was established by Ratana apostle and then minister of Maori Affairs Matiu Rata which from 1975 began looking into Maori grievances.

To date over 90 settlements have been made totalling around $2.5 billion and in all likelihood that could reached up to $5 billion by the time the last settlements have been agreed to.

That number pales when we consider the value of what was taken, the cost of survival in the time of Covid or even the Corrections budget of keeping people in prison for the 2020-2021 year which was $2.4 billion.

When most people think of the Treaty of Waitangi and its three main paragraphs upon which our nation was founded, they mostly think of the money spent in meagre compensation but fail to consider the generational damage and lost trust that resulted from that promising relationship being broken so soon.

The original treaty documents were lost before being redeemed from the rats both literal and metaphorical. Perhaps, while final settlements are still being sorted, we need to rediscover whether the original intentions still resonate?

If that means respect and celebrating our shared humanity as treaty partners, rather than being polarised behind walls of difference in times of massive change, then there’s some serious work needed to heal our nation in order to forge a fresh vision for a more hopeful future.

See part Two: Reframing the conversation

By Keith Newman (02-02-22)

Aotearoa-New Zealand might not have a cohesive constitution or a clear mission statement but we do have three hurriedly translated, often misinterpreted paragraphs, that provide the foundation promises for forging a formidable future together.

Alongside that founding document there’s an equally misunderstood statement, sealed with a hongi and a handshake, that urges Maori and Pakeha to look past the barriers of difference and work together for the common good.

On 6 February 1840, British officials and church leaders including Church Missionary Society head Henry Williams and Catholic Bishop Pompallier were at Waitangi in the Bay of Islands to witness the Treaty of Waitangi being signed by Maori chiefs and the Crown.

Maori wanted protection from the lawlessness of whalers, sealers and traders and were concerned that private investors were claiming enormous quantities of land for blankets and buttons, pots and pans, tobacco, gunpowder, tools and small amounts of cash. There was also the very real possibility of the French making a claim to the country.

The treaty promised Maori exclusive and undisturbed possession of their lands, estates, fisheries and forests as long as they desired (tino rangatiratanga/ chieftainship). Their land could only be sold at agreed prices through the Crown (pre-emption). In exchange Maori would concede elements of governership (kawenatanga) or sovereignty, terminology that is still the subject of heated debate.

Queen Victoria, representing the Church of England, promised Maori protection and equal rights and privileges alongside British citizens. Maori looked forward to more lucrative trading opportunities, confident their lands would be protected unless they wanted to sell and saw this new relationship with the Queen as affirming the biblically-based principals behind 30-years of missionary teaching.

This was not an invasion or colonising in the sense of how Britain had dealt with countless nations previously. This was a deal with a very intentional Christian undercurrent to ensure such colonizing atrocities on indigenous people, never happened again.

Maori, based on the He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tireni (Declaration of Independence of the United Tribes of New Zealand) signed with Britain five years earlier were an independent people with their own form of agriculture and tribal governance.

Ultimately 540 Māori chiefs signed nine copies of the Treaty of Waitangi, including 13 women; all but 39 signed the Maori version.

While the Treaty assured equality with British citizens, French Bishop Pompallier wasn’t entirely happy with the thought that the recently arrived Catholics might be sidelined so he insisted on a fourth clause covering freedom of religion.

This often ignored ‘phantom clause’, written down on the day and recorded by William Colenso in his report but not signed as part of the Treaty, may yet prove as invaluable as other oral history.

Peaceful alliance

A treaty is often viewed as a peace alliance and this one was a peaceful bilateral agreement. It was certainly not the signing over of everything one party had to the other.

Once Maori signatures or tohu (symbols) were placed on the treaty document that first Waitangi Day, Governor William Hobson greeted each chief with a sincere He iwi tahi tatou. That’s had various interpretations imposed including ‘Now we are one people’. In recent years it has often been written as He iwi kotahi tatou which affirms that interpretation but has added to the confusion.

Some writers, including Danny Keenan go so far as to suggest Hobson never made that statement and it was added later by eye-witness to the events, missionary printer William Colenso. And of course the term has come into disrepute because of its use by the ‘Kiwi not Iwi...one New Zealand’ advocacy group Hobson’s Pledge which holds to a literal interpretation opposing any hint of ‘Maori privilege’ including separate political representation.

Social anthropologist and writer Dame Joan Metge doesn’t seem to have a problem accepting what Hobson said but suggests it might be better understood to mean “We two (many) peoples together make a nation”. Another scholarly Dame, researcher and writer Ann Salmond views the treaty as “...a chiefly gift of exchange” involving shared humanity, reciprocity and respect.

Ngāpuhi elder Waihoroi Shortland stepped into the debate at the Waitangi Day commemoration in 2020 when he challenged Governor-General Dame Patsy Reddy insisting it was time to address the modern misuse of Hobson’s words. The words Hobson was “encouraged to say” were, ‘he iwi tahi tātou’. “He did not say, ‘he iwi kōtahi tātou’.”

It was an unresolved issue that needed to be corrected. Shortland said the northern tribes understood the difference, and it related to the uniting of Maori and Pakeha. He translated them for the Governor-General as, ‘Together we are one nation’.

Who influenced Hobson?

Stepping back in time we might ask where the phrase He iwi tahi tatou came from? Was Captain Hobson simply ad-libbing or ‘encouraged’ to say those words as Shortland suggests.

There’s every indication the source of that encouragement was Henry Williams, who with his son Edward translated the Treaty of Waitangi virtually overnight, having just arrived back in the Bay of Islands after travelling overland from the Kapiti Coast.

The original treaty instructions to be interpreted in te reo Maori had come from the James Stephen Jnr, permanent under-secretary of the Colonial Office, a committed Christian and the nephew of William Wilberforce, British Parliamentarian, slavery reformer and mentor to Samuel Marsden.

Williams drew on biblical concepts and his previous effort in translating He Whakaputanga for the treaty clauses and the suggested Maori words for Hobson to affirm the signing would not have been chosen lightly.

Hobson’s so-called pledge had him quoting from Galatians 3:26-29 where the Apostle Paul says “for you are all one”. The context makes it plain that this is about becoming sons and daughters of God through faith in Christ, and that the unity being spoken of is a spiritual connection that does not favour one people group over another.

Taking the phrase literally creates immense difficulty and confusion if we read the rest of the verse, which states that those who embrace this challenge are now “neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female”.

Maori, who had sat under the missionary teaching for over 26-years, would have known that this treaty was about becoming part of something new that was not based on old tribal divisions.

The treaty wasn’t simply signatures on a piece of paper, it was a spiritual and political covenant, a marrying of two peoples, with an expectation that both would benefit and do amazing things together with their shared energy and resources.

Maori voice silenced

All good covenants and treaties, and indeed marriages, require ongoing conversations to check on progress, to determine if the conditions are being fulfilled and concerns addressed. For Maori that failed to happen.

Despite the best intentions of those wrote, promoted and signed the treaty it’s basic promises and the affirmation of unity were soon betrayed. New Zealand was essentially being run from New South Wales and Hobson and his band of officials had little funding or support to run this new outpost of empire.

From about 1843 onward the treaty seemed of little importance and people like Henry Williams who helped transcribe it were dismayed at the failure of the Crown and its representative to honour it as clear breaches were ignored and armed confrontations escalated.

Massive land sales were being transacted and often the promise of adequate reserves and hospitals and schools disappeared as quickly as the surveyors arrived. The pressure remained to acquire tribal land, break customary ownership and force individualisation of Maori title to meet the demands of settlers.

The initial problem was created by the New Zealand Company which had sold what they hadn’t yet properly purchased before Crown land purchasing officers began engaging in similar underhand tactics.

The Treaty of Waitangi was an obstacle to greedy politicians, lawyers and land agents acquiring lands as cheaply as possible and then on-selling it for profit to top up government, individual and investor coffers.

The Maori voice was effectively silenced. Even a long line of advocates including the Williams brothers, Colenso, Octavius Hadfield and later Maori prophets and kings achieved only a token hearing when they raised concerns about the obvious betrayals and injustices.

When Maori began to resist, organize, question, challenge and pull out surveyor’s pegs, military campaigns were mounted by successive governors with tactical laws passed that supported dispossession, including confiscating ‘rebel’ land in the richest parts of the country.

Retrieved from the rats

There was little conversation about the Treaty of Waitangi in the years after it was signed. Promises of gatherings to discuss next steps never happened.

There was no hint in the four original treaty clauses or the four words that sealed that deal with a handshake and a hongi of assimilating Maori into a colonial melting pot, as some future administrators imagined when they essentially excluded Maori from the 1852 Constitution Act and spoke of “fluffing up the pillow of a dying race”.

The treaty was soon forgotten, lost, nibbled at by rats and saved from a fire. In 1877 it was undermined in the courts when on high court judge declared it “a simple nullity” because ‘the savages’ who signed it could never have understood what they were doing.

But Maori were resilient and determined to ignore the false prophecies and despite being worn down by war and deception new visionary leadership set them on a road to restore their rightful place in the land they one called their own.

Maori prophet Tahupotiki Wiremu Ratana and Kingitanga leader Tupu Te Waharoa raised a petition with full evidence of treaty breaches, signed by two thirds of all Maori (40,000). Despite efforts to undermine it in England and in New Zealand, it was eventually tabled in Parliament in 1932 with the proposition that it be ratified and included in the laws of the nation. Still, it languished.

Then the Treaty of Waitangi became the heart of the Maori renaissance of the 1970s when a new generation of activists could no longer tolerate the duplicity. The Waitangi Tribunal was established by Ratana apostle and then minister of Maori Affairs Matiu Rata which from 1975 began looking into Maori grievances.

To date over 90 settlements have been made totalling around $2.5 billion and in all likelihood that could reached up to $5 billion by the time the last settlements have been agreed to.

That number pales when we consider the value of what was taken, the cost of survival in the time of Covid or even the Corrections budget of keeping people in prison for the 2020-2021 year which was $2.4 billion.

When most people think of the Treaty of Waitangi and its three main paragraphs upon which our nation was founded, they mostly think of the money spent in meagre compensation but fail to consider the generational damage and lost trust that resulted from that promising relationship being broken so soon.

The original treaty documents were lost before being redeemed from the rats both literal and metaphorical. Perhaps, while final settlements are still being sorted, we need to rediscover whether the original intentions still resonate?

If that means respect and celebrating our shared humanity as treaty partners, rather than being polarised behind walls of difference in times of massive change, then there’s some serious work needed to heal our nation in order to forge a fresh vision for a more hopeful future.

See part Two: Reframing the conversation

RSS Feed

RSS Feed